What is a hut? Towards a definition (2015)

What is a hut? Is it a hovel, a shelter, a hostel, or a hotel? Quick answer: all of the above, and much more. In everyday useage it is a catchall term for forms of shelter and specific definitions are elusive. These are notes towards a workable hut definition.

We’ll touch on the most common definitions and perceptions of the term “hut”, then focus specifically on the use of the term in the context of long distance walking. My purposes are to briefly illustrate the wide range of huts for walkers (and skiiers & bikers, which are lumped into the terms hikers and walkers here) and to attempt an initial typology clarifying the uses of the term.

Most people think of huts — especially in cultures where recreational long distance walking is not common – in terms of the definition in the Oxford English Dictionary:

A dwelling of ruder and meaner construction and (usually) smaller size than a house, often of branches, turf, or mud, such as is inhabited in primitive societies, or constructed for temporary use by shepherds, workmen, or travellers. In Australia, applied to the cottages of stock-men.

The all-purpose term “hut” is used to encompasses numerous shelter types of “primitive” vernacular architecture, including: barracks, bivouacs, bothys, cabanas, cabins, casitas, chizos, follies, hermitages, ice houses, igloos, lean-to’s, lodges, milking and cheese making houses, shacks, shantys, shelters for walkers, storage buildings, tea houses, tents, tipis, wooden sheds, workshops, writers or hermits cabins, and yurts. Historically, huts tend to be built of local materials and shelter nomadic peoples or folks temporarily working in the back-country (i.e. used for a few days or a season), such as: shepherds, herders, foresters, miners, stockmen, hunters and fishers. The term is also used to denote wretched permanent dwellings, also called hovels.

Writer Gaston Bachelard, who describes huts as “the tap-root of inhabiting”, best captures the gestalt of the hut. In essence a hut equals a roof and a wind-break, a place of refuge. Huts fill the essential human need as a place of shelter from the elements.

Over the centuries these rustic shelters have piqued imaginations around the world, and have gradually taken on less prosaic associations. My intent is to help preserve and celebrate the tap-root, while cheering on and cultivating flourishing styles and all that relates to this wonderfully ambiguous, adaptable and diverse building type.

In A hut of Ones Own (MIT Press, 1998), architect Ann Cline locates huts on the “borderlands of architecture”. Not generally included within the circle of formal architecture, huts exist on the margins as inescapable progenitors and goads to architecture. Cline gives three examples of the sweet, sacred and profane hut images prevalent in the popular imagination:

Heidi, inhabiting the mountain hut as an idyll of alpine pastoral existence;

Ascetics and hermits, escaping the traces of civilization to exist in a purer state closer to and nature; and

Lady Chatterly and her lover, succumbing to their “natural desires” in a gamekeepers hut.

Dianne Johnson’s quirky and delightful book Hut in the Wild (http://www.loveofbooks.com.au, 2011) explores the hut as an archetype, “a cabin of the imagination, and inscape, it is redolent of a lost paradise regained, a gleaner’s bliss….and sometimes a place of hospitality.” There is a much deeper story to be told about the close and distant cousins to hikers huts, but thats for a different article.

Walkers adopt the term hut. At some point European walkers began to use the term “hut” (in other languages: hutte, hytte, refugio, cappana, etc.) to describe a range of shelter types used to support long distance walking. How did this adoption happen? Here are a few threads of the story.

Long ago, pilgrims and other walkers sometimes took shelter in huts developed for others (shepherds, hunters, etc.). The growing popularity of religious pilgrimage stimulated the early development of purpose-built hostels in support of long distance walkers. Merchants and other travellers relied on existing shelters in their travels between towns. In the nineteenth century European alpinists, in Switzerland and elsewhere, began to use shepherd huts as staging shelters in their pursuit of peak-bagging. Gradually an informal pattern of commerce developed as alpinists paid farmers for temporary use of these alpine shelters. Walkers of the Romantic era soon realized they could extend their walks with overnight shelters. Recreational walking and alpinism flourished side by side, and eventually alpine clubs were formed (the Swiss Alpine Club was founded in 1863). These clubs sometimes incorporated existing huts and began to build new ones, added on over the years, and gradually developed a remarkable infrastructure in support of mountain walking.

So the use of huts by walkers developed by necessity (shelter for travelers between towns) and also by imaginative re-use of what might be called “infrastructure lying in wait”. Around the world walkers have gradually appropriated structures (and terminology) first built for other purposes. Australians in particular have lovingly restored and repurposed for walkers and skiers a great many huts. Many mountain huts are essentially hostels in the mountains, and the most elaborate are classy hotels. Hiking inn to inn and B&B to B&B, constitutes a trail system designed around existing hotel infrastructure.

hut2hut.info is based on the premise that a new generation of hut systems will be built in the USA over the next 20 years, and will develop in part around “infrastructure lying in wait” – a term suggested to me by hut-master Rob Stenger — such as existing long distance trail systems and a wide range of huts, shelters, cabins, lodges, yurts, and tipis, & camps.

Towards a typology of huts

The term “hut” has come to describe an extremely diverse range of shelter. Casual walkers are often confused as to what is meant by the term. No wonder: huts range from primitive shelters, to alpine bivouacs, to walkers hostels, to fancy mountain hotels. Some are part of a hut system that is designed to support walking along a designated trail. Others are stand-alone, used as base camps for day trips.

Usages are regional and overlapping. As an example, in Forest and Crag (Appalachian Mountain Club, 1989), on p. 382 Laura and Guy Waterman explain termin0logical practice in relation to shelter types in Northern New England:

….the words used to denote backcountry buildings have taken on more or less precise meanings. Three-sided overhanging-roof constructions, with or without floors, are usually called shelters, or less often lean-tos, or generically Adirondack lean-tos. Four-sided closed buildings, with a door and wondow(s) are called cabins, camps, or (especially the larger ones in Vermont) lodges. All of these, however, presuppose self-sufficient hikers, carrying their own food and usually, though not invariably, their own cook-gear and bedding. In New England the term [huts] is normally reserved for that unique backcountry building where a resident crew provides the food and does the cooking. They are, in in effect, primitive off-road inns.

It may be useful to examine types of huts for walkers and attempt to clarify the variety of huts with a typology.

To clarify the wide variation in terminology, the characteristics to take into consideration in categorizing huts include:

are they open (e.g. three-sided) or closed to the elements?

since they come in all shapes, sizes and styles, from very rustic to high architecture, what is the nature of the structure? Are they more like simple shelters or like hostels or hotels?

are they comfortable and cozy, or spartan in look and feel?

are they staffed or unstaffed?

do they provide for self-service cooking, or are meals provided?

do they provide beds or simply a designated place for sleeping bags?

do they have full bathrooms, outhouses, or pit toilets?

do they provide electricity and hot water?

do they provide amenities such as beer and wine service, cafes, , saunas, libraries and game rooms, drying rooms and more.

Alot is loaded onto one word: hut! How do we clarify what we mean when we say hut? Wikipedia, the Norwegian Trekking Association (Den Norske Turistforeningen or DNT), Austrian Alpine club (Österreichischer Alpenverein or OeAV) and German Alpine Club (Deutscher Alpenverein or DAV) provide some initial typologies. There are doubtless others I haven’t seen and would very much appreciate hearing from readers.

Wikipedia has useful entries on Hut, Backcountry hut, Bothy, French dry stone huts, Lean-to, Log cabin, Mountain hut, Primitive hut, Wilderness hut, and Yurt. In relation to walking and skiing, the articles seem to distinguish between shelters located in mountain environments and those located at lower elevations and provide examples of various kinds of huts and shelters.

The OeAV and DAV distinguish three levels, the first of which is for walkers and climbers, and the second and third either accessible by or can be provisioned from the road.

The DNT typology is useful in defining a variety of hytte (hut) types. Quoted from their website:

Staffed lodges serve breakfast and dinner. Many have showers and electricity, either from the power grid or from a local generator. The staffed lodges are open only in certain seasons. Many staffed lodges have self-service or no-service cabins for accommodation out of season. The self-service facilities are not available when the lodge is staffed in season.

The self-service cabins are equipped with all that trekkers need for cooking and sleeping. Firewood, gas, kitchen utensils, table linen and bunks with blanks or duvets and pillows (hut sacks, also known as hut sleepers, are required!) The cabins are also stocked with provisions including tinned goods, coffee, tea, rye crispbread and powdered soup packets, but the selection can vary from cabin to cabin. Here trekkers look after themselves: fetch water, cook food, wash up and chop wood. In high seasons, some cabins have wardens that assist in organising work. You can pay by direct debit single authorization or by a bank giro drawn on your account. Many self-service cabins are closed for periods during the year.

No-service cabins usually have the same equipment as self-service cabins, but they have no provisions. There also are a few simpler no-service cabins where you’ll need a sleeping bag and perhaps more equipment. The descriptions of the cabins include specifications of their equipment. Some of the no-service cabins are closed for periods during the year.

A preliminary typology for hut2hut.info

Building on these two models, I propose a preliminary typology based on the type of accommodation and whether or not they are located on a trail system. We will use this simple three-part hut taxonomy in HutMap of North America , and will modify as we learn from experience.

Full service hut and yurt systems (hutte, hytte, refugia, etc.)

Hut systems that comprise groups of 2 or more huts, intentionally spaced a days walk apart on a designated trail system. They are designed to support walks ranging from several days to months on end. And they generally provide space for eating and social interaction.

These systems may be further subdivided according to whether they are:

staffed or unstaffed,

provide meals or cooking facilities, or at least a place to set up your stove;

provide beds (ranging from individual rooms, to dormitories, to metratzenlagger) or, more rustically, designated places to put down your sleeping bag.

Examples in the USA include 10th Mountain Division Huts in Colorado and Appalachian Mountain Club Huts in New Hampshire.

2. Shelter systems are often three sided structures located along established hiking trails. They are usually unstaffed, rent-free, and used by backpackers. Examples in the USA include the Appalachian Trail and Long Trail.

3. Stand-alone huts, cabins, lodges, and yurts that are not connected as part of an intentional system for walkers exist in a wide range of configurations. Many are used as base camps for day hikes. Examples in USA include Appalachian Mountain Club’s lodges, Opus Hut in Telluride, etc.

Gorman Chairback central lodge.

Credit: Dennis Welsh, Courtesy of AMC

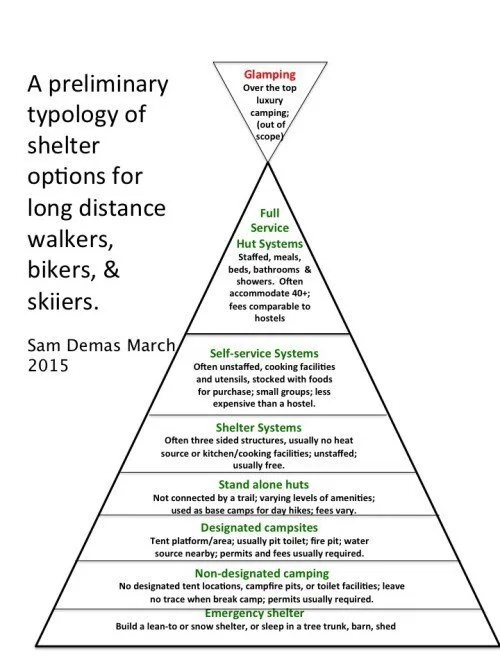

While this preliminary typology may seem logical, it doesn’t really represent the full complexity of huts. For example, it is not unusual for the huts in a single system to vary significantly and seasonally in whether they are staffed and in the amenities provided. Here is a different representation of the same typology (with apologies to Maslow), but providing a bit more context and nuance on the choices walkers have.

Shelter types: where is a traveler to stay?

Even this chart does not capture the full set of possibilities. But, it is a start. Readers are invited to submit their own definitions and typologies.

Is the American confusion of huts with hovels a problem? No, I don’t think so.

However, it is a marketing challenge for some hut managers in the USA. Most Americans still don’t have a clue about huts for walkers. They are amazed to learn about the ubiquitous, comfortable huts of Europe. They may be attracted to the romance of a mountain hut, but cringe at the idea of staying in one. Alas, by getting stuck on the OED definition they are missing out on a great deal of fun!

The best way to learn the difference between a hovel and a hut is to spend a few nights in a hut. I hope perusing hut2hut.info will help a bit in developing a broader understanding of the amazing world of huts.

***********

hut2hut.info will continue to explore the world of huts that springs from the tap-root of architecture. Your comments and contributions are welcome on topics such as:

Reporting on examples of imaginative design and architecture;

Illustrating the continuum of existing shelter types for walkers; and

Refining our understanding and the semantics around shelter for walking and developing a useful typology.

Share with me your thoughts on huts and comments on my preliminary typology.

Sam Demas, Editor, h2h

sdemas@carleton.edu