New Zealand Hut Operations: Notes on ten selected DoC hut operations

New Zealand Huts Department of Conservation, Part D:

Notes on Ten Selected Operations

by Sam Demas

(Note: this is part of the larger work New Zealand Huts: Notes towards a Country Study)

New Zealand hut operations: a comprehensive view and analysis of DoC hut operations is beyond the scope of my time and capabilities. Instead, following are notes on operational features I found particularly unique, interesting, and/or instructive. The intent is to convey an introductory overview — hopefully a helpful point of entry — for people outside New Zealand who are interested in learning how DoC operates its huts. This information was gleaned from reading DoC documents and from three months in New Zealand tramping and talking with folks.

Economics: what does it cost to operate the DoC huts?

Click on title above for a brief synopsis of costs and revenues based on conversations with Brian Dobbie, Technical Advisor, Recreation, Heritage and Technical Unit, DoC Central Office, Wellington.

Tracks

In New Zealand the term “tracks” is used in the way “trails” is used in USA. The geology, climate and vegetation of New Zealand often conspire to produce rugged tracks challenging for both trampers and for those responsible for track maintenance.

Rocks, roots and mud make for tough, walking conditions on many backcountry tracks. Foreigners new to NZ tramping need to recalibrate what it means to walk 10 kilometers in the mountains. This has implications for safety, and for pressure on search and rescue crews besieged by calls to rescue inexperienced trampers. But that’s another topic altogether!

Extent of DoC Tracks

According to Brian Dobbie, in 2018 DoC operates 14,796 km of tracks, broken down as follows in the categories described in Part 1 above. The length of DOC track in each category is:

Short walk – 183 km

Walking track – 2,591 km

Easy tramping track – 941 km

Great Walk – 399 km

Tramping track – 8,882 km

Route – 1,800 km

Total 14,796 km

Track Maintenance

Tracks used to get from hut-to-hut – Tramping tracks and Routes — constitute about 72% of DoC’s tracks. These are among the most remote tracks in New Zealand and present a challenge in terms quantity and difficulty of track maintenance. On the other hand, only 2.7% of the DoC track is for Great Walks. A number of Kiwi’s commented that the Great Walks tracks are privileged for maintenance because they constitute an important income stream for DoC and New Zealand generally, and because they cater to a large degree to less experienced hikers from abroad.

While individuals, tramping clubs, the Backcountry Trust, and other groups volunteer to help maintain this nearly 15,000 km of tracks, my impression is that most track maintenance work is performed by DoC regional staff. While DoC advertises volunteer needs on their website, it seems that the culture of volunteerism in relation to track maintenance is still under-developed in comparison with the U.S., for example, where 94% of trail maintenance is performed by volunteers. I heard from some active trampers that they are leery of getting into the potentially vulnerable position where the vast majority of track maintenance is performed by volunteers. This could result in DoC diminishing its capability to maintain the tracks, to the point the system could be endangered if increased volunteerism later drops off. Finding the right balance is a key.

A one sheet DoC handout, Guide to Track Clearing, provides a concise overview for staff and volunteers of some key track maintenance standards.

Track building

The growth area for DoC track building (and for NZ in general it seems) is in cycling trails. DoC developed Track Construction and Maintenance Guidelines in 2008, which supplement HB 8630:2004, NZ Handbook Tracks and Outdoor Structures described in Part 1 above. While HB 8630 specifies the standards for tracks it does not explain methods for how to achieve the m, and it treats the design and construction of cycle tracks as well as walking tracks.

DoC works in partnership with many groups interested in track building, including cycling groups. Several DoC staff participated as reviewers of Track Construction and Maintenance Guide, (Via Strada, Ltd. 4th edition 2015), a 95 page document prepared for the NZ Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment, This document provides information on the construction and maintenance of recreation tracks for walkers and off road mountain bikers.

Waste Management: toilets, human waste and gray water

Toilets

All DoC huts include toilets, always located outside the hut. [Apparently there are some Basic Huts that historically haven’t had toilets; these may be required to install them if during inspections it is determined that the extent of use and local conditions indicate the need.]

See on the web an overview of backcountry waste methods presented by Tom Hopkins of DoC and John Cocks of MWH Global.

The most common toilet systems by far are pit toilets and vault (or containment) toilets. Both of these types of toilets are vented. Some Great Walks huts have flush toilets with septic systems. I’m not sure the extent of composting toilets in DoC huts. Apparently there is some experimentation going on with vermi-composting in a few huts, but an unresolved issue is the introduction of exotic invertebrate species.

“Hut Procurement Manual, Part F” provides specifications for “Ventilation Improved Pit Toilets”, including: 7 pages of specs for the number, location, orientation, capacity, ventilation, lighting and insulation, and cubical construction; and 4 pages of construction drawings. Most pit and vault toilets have molded plastic/fiberglass tops/sitting chambers and vents, making them lighter to transport in, easy to install, and easy to clean.

It is interesting to note that on tracks that are over-run with tourists, e.g. N. Tongariro Crossing, temporary toilets are flown in by helicopter and placed along the track for the season. Not a sustainable situation!

There was a line of over 40 trampers waiting for access to one of these temporary toilets on N. Tongariro Crossing.

Human waste disposal

The most common waste disposal systems used are: 1. helicopter removal by sucking the waste from containment tanks, 2. small containment tanks on rail systems to allow helicopter removal of whole tank when full, 3. composting toilets, and 4. hybrid systems using septic tanks and leach fields for liquid waste, while containing solids which are pumped out periodically.

Helicopter removal of waste is probably the most common method of waste removal.

Pit toilets are used at huts that are not frequently visited, or that are sited in an inaccessible locations, or in situations in which it is difficult to work/dig. They are frequently dug with pick and shovel, and sometimes with the assistance of dynamite. When pit toilets become full the waste is buried and the toilet moved to a new location.

Huts in the alpine zone present special challenges. There is discussion of, but not much optimism for the practicality of implementing strategies for alpine hut users to pack out their own human waste.

Vault toilets are increasingly common, particularly in the newer huts and those with the highest level of amenities. These have an encased vault that effectively contains the waste. They are designed to permit pumping of waste into storage containers, which are flown out by helicopter to join the waste stream at a sewage treatment plant. There are occasional problems with ice and snow fouling the pumping works, but this system seems to be becoming the norm in newer huts. Helicopter removal is expensive and there is increasing sensitivity to the noise generated by aircraft, particularly in proximity to wilderness areas. Increased use of certain huts and tracks is results in vaults filling quickly and needing to be emptied frequently.

Gray water treatment and disposal

Wastewater discharged from a sink or basin at a hut runs through a gully trap and into a gray water treatment and disposal system. The specifications for these systems are detailed in “Hut Procurement Manual”, Part F. The criteria for determining the suitability of a septic tank, compared with a soil soakage pit or bed include soil type, terrain and size of the hut (number of bunks).

Water supply

DoC is required to provide clean, but not necessarily potable water in its huts. The distinction seems to be based on the facts that: 1. it is not feasible for DoC to test and certify the potability of water at all huts with great frequency, 2. reported cases of non-potable water in and around huts are very rare, 3. backcountry adventure and remoteness seekers are expected to have the knowledge and skills to ensure their own safety, and 4. the practice of drinking untreated water in the backcountry is widespread and accepted by trampers in New Zealand.

The last two reasons cited above – trampers are responsible for their own safety, and people drink water in the backcountry at their own risk – are related to a distinctive feature of the NZ legal system: it bars most forms of personal injury claims. This freedom of DoC and other outdoor operators from liability law suits is a remarkably sensible and liberating factor in organizing and conducting outdoor recreation activities in NZ.

Standard, Serviced, and Great Walks huts contain signs near water taps stating that the water is clean and able to be drunk without treatment, but that users may, for their own protection, wish to boil or treat the water:

Water supply sign in most DoC huts.

The primary sources of drinking water for the huts are:

Rainwater collection from hut roofs,

Piped (usually gravity feed) to the hut from a natural watercourse,

Direct from a year-round water-course within 50 meters of the hut for Serviced Huts, standard huts, within 100 meters for Standard Huts, and within 200 meters for basic huts.

Snow and ice melt is acceptable source for Alpine Serviced huts.

While Giardia is common in New Zealand, its seems that backcountry streams are largely untainted; this may be due to the comparative scarcity of mammals in the bush. NZ trampers universally fill their water bottles and cook with untreated water directly from backcountry streams. While many foreigners quickly adopt local practice, some continue treating their water at the huts.

Rainwater collection systems are the predominant source of water in the huts. Specifications for design of these systems are detailed in Hut Procurement Manual, Part E, section E3. This comprises five pages of specifications, followed by a three-page appendix with detailed construction drawings.

Components of these gravity feed rainwater collection systems include hut roof and gutters, an elevated rain water storage tank, and supply outlets, which may or may not be discharged over a sink. Roofing materials include unpainted zinc/aluminum coated or galvanized steel, stainless steel, aluminum, and PVC (without lead stabilizers) or fiberglass sheeting. Also specified are acceptable roof paints/coatings, gutters and downpipes, water pipes, and fittings. In geothermal regions where there is a risk of eruption and ash fall accumulating on roofs, consideration of a system for temporarily disconnecting roof collection systems is advised.

Supply of hot water in the huts is rare, confined primarily to some of the Great Walks huts. In some Great Walks huts a hot water spigot is provided at the sinks for use in dishwashing. In some huts (e.g. the New Waihohonu Hut in Tongariro), water is heated as part of the operation of a gas heater for warming the common areas. Use of solar panels to heat water seems to be rare. Showers, deemed a luxury, are not provided in any DoC huts.

Sinks for food rinsing/dish washing and for hand washing are required for Great Walks Huts, Serviced Huts, and Serviced Alpine Huts with more than 1,000 bed nights per years. Food rinsing/dish washing sinks are generally located near the food preparation area, while sinks for hand washing and tooth brushing are generally located outside the but or in association with the toilets. Sinks for standard huts are located outside the hut.

Intentions books (aka logbooks/visitor books) and graffiti

As in huts around the world, logbooks are standard in DoC huts. Before DoC existed, various clubs and government agencies provided hut logbooks for visitors to sign and comment. The impulse to record one’s presence, I call it the “I was here” impulse, seems fairly universal and extends beyond hut books to graffiti on hut walls, roofs and timbers. Following is a bit of information on these fascinating historical documents.

DoC Intentions Books

The green-covered DoC logbooks are called Intentions Books , apparently signaling a chief DoC interest in the genre: to provide information in search and rescue operations.

Twelve column DoC Intentions Book

The twelve columns are labeled:

Date of arrival

Number of nights at this hut or state “day visited”

Number of people in group

Office use only (leave blank)

Names of group members

Backcountry Hut Pass number (for all group members)

Hometown (and country if not from New Zealand)

Date and time of departure from this facility

Date due out from this trip

Trip intentions. Main activity and planned route and destination from this facility.

Current weather conditions

Comments and observations (e.g. hut/track conditions, wild life)

Columns 8-11 provide information in case of search and rescue operations. These data provide clues to help narrow the search. [An interesting fictional treatment of how search and rescue is conducted and how this information is used may be found in The Intentions Book by Gigi Fenster (Victoria University Press).] See photos of the 16 pages of Intentions Book front matter, which focus largely on safety matters.

The logbook data is used by DoC for data collections purposes, including calculating the extent of use of huts. Unfortunately not all visitors sign logbooks, in some cases to avoid paying hut fees. I have heard estimates of 25% – 50% of visitors who do not sign the Intentions Books. In some remote huts the same Intentions Book serves as a visitor record for many years, while in busy huts new books are provided frequently as they fill up.

An important functions of logbooks are to communicate useful information about the hut and track, and also for the amusement of visitors. In the evening many trampers enjoy looking through the list of visitors, finding folks they know or seeing where visitors are from, and writing comments about all manner of topics. These comments often spark responses by others and form a kind of ongoing conversation among denizens of the huts. These logbook pages become part of the cultural history of the bush.

Alas, the “comments” column is very constrained in DoC logbooks. Making more room for comments would likely yield useful (and yes, also not-very-useful) information for DoC and researchers. But fortunately people frequently “color outside the lines” in conveying their responses to the bush and the hut experience.

In New Zealand (see Kearns, Robin and Fagan, Joe, “Sleeping with the Past? Heritage, recreation, and transition in New Zealand tramping huts” in New Zealand Geographer (2014) 70, 116-130) and elsewhere logbooks are used for research purposes.

Preservation of logbooks

DoC regional staff collect the Intentions Books when they are full, analyze the data as needed and send them to the DoC library where they are processed as historical records. It seems that Archives New Zealand is the primary repository of DoC logbooks. I did not delve into this important genre, but was pleased to learn that Bill Keir has compiled an “Archive Inventory” that goes a long ways towards documenting the status of pre-2000 hut logbooks. A 2012 article in FMC Bulletin provides further information.

Historic graffiti

Another category of cultural heritage records in the huts is the ample graffiti scrawled on the roofs, beams and tin walls of huts. It turns out lead pencil on tin in a hut interior is a fairly enduing form of writing. Mark Pickering has written about historic hut graffiti (e.g. Sir Edmund Hillary, Lord Bledisole, a former governor general of NZ), some of which goes back to the 19th century. In its historic preservation work DoC goes to some lengths to preserve historic graffiti in situ and/or to use it in interpretive panels.

Historic huts and hut conservation

While New Zealand is not unique in celebrating its older huts, it appears that the extent of hut-related research and active preservation/conservation efforts is much greater than in other nations. This commitment to huts as heritage is a clear indication of the age, variety, extent, significance, and respect/affection for huts in NZ. The remarkable work of citizen groups and the related establishment by DoC of the Backcountry Trust are discussed in the following section. This section briefly notes examples of DoC heritage conservation work through its own staff efforts.

Before discussing formally designated heritage huts, check out a sentimental gallery of photos of some of the older huts I visited that, while they may or may not have formal designation as historic huts, give one a good sense of the qualities of huts that many Kiwi’s treasure. These are not “flash”!

The reasons for the unusually strong connection that Kiwi’s feel with huts as part of their cultural heritage is discussed elsewhere in these notes. But know that the widespread national impulse to affection and protection repeatedly manifests as expressions of concern, and sometimes outrage, when DoC proposes to eliminate or downgrade the maintenance of beloved huts. As part of its responsibility for so many old and well-loved huts, DoC has developed internal capacity and strategies for historic preservation of huts. This includes both published research, recommendations and analysis, as well as actual field preservation work. Historic preservation also takes the form of interpretive signs and installations in historic huts.

DoC’s research and analysis on hut preservation is carried out by heritage specialists in the districts. While I did not meet them, the names most frequently encountered are: Steve Bagley (Nelson), Jackie Breen (West Coast), Rachel Egerton (Southland). The on-site construction/restoration work on huts that allows trampers to stay overnight in huts restored as living history is conducted by DoC Rangers in various districts. I had the pleasure of talking at length with several Rangers in the Golden Bay District (which has accomplished some excellent hut preservation work), including hut preservation pioneer John Taylor (see separate “hut hero” profile). Following is some general information about and a few representative examples of DoC hut heritage work.

Heritage huts

On its web site DoC lists 81 historic huts under active DoC management. This partial listing of historic huts represents vernacular architecture initially developed for wild animal control, sheep mustering, recreation, schools, and a variety of other uses. Many of these are in active use by trampers as living history sites. The largest concentrations are in Golden Bay and Canterbury. These 81 huts are said to be part of a representative sample of historic huts under development.

There are many more historic huts one can explore. Just as a few examples, following are more “historic” huts (or replicas/reconstructions) with which I (as a complete novice) am familiar from my travels that are not included on the list of 81 cited above:

the Arrowtown Chinese gold miners huts in central Otago (these are living museum pieces and not open to trampers),

In Golden Bay area: the Soper Shelter, Riordan’s Hut, Tin Hut Shelter, Ministry of Works Hut, Anatoki Forks Hut, Chaffee Hut, Cobb Valley Tent Camp., and Tin Hut.

A small sample of historic huts:

The experience of visiting – and particularly of staying overnight in an historic hut, whether it is an original or a replica, or whether or not it meets the necessarily very specific criteria used by heritage preservation specialists — is magical! Fortunately, there are many opportunities to visit and stay in such huts in New Zealand. While many are in remote locations, many are not. In my experience, it is worth the effort to travel back in New Zealand history in this very visceral, memorable way.

Historic heritage assessments and other publications

Following are three examples of the kinds of hut-related publications produced by the DoC heritage officers. Reflecting DoC’s broad brief in heritage identification and assessment, these reports tend to begin by locating the analysis of a category of huts in a broad thematic heritage framework, and defining the scope of the analysis. It then goes on to provide an historical overview of the particular category of huts, or specific hut, telling the story – in text and illustrations — of how they came to be, how they were used over time, and how they relate to New Zealand history and culture. They provide anecdote, data, agency context, relevant notes on construction methods and materials, and they may include management recommendations, threats, original hut designs, recommendations for further work, ranking and/or criteria for assessment of huts to be protected. They tend to be about 35-50 pages, contain fascinating historical detail, and make for quite interesting reading. Most of all they give valuable insight into the value of historic huts and the challenges in preserving them. Try one!

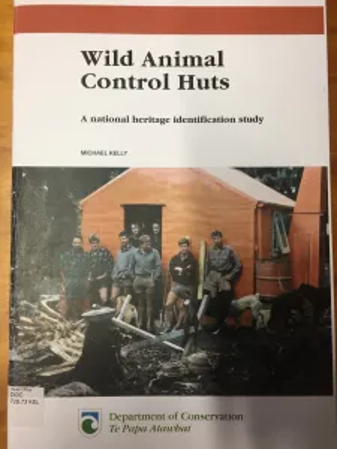

One of the assessment reports most frequently cited was authored by heritage consultant Michael Kelly: Wild animal control huts: a national heritage identification study. It helps greatly in understanding an important thread in the development of NZ huts and backcountry life.

Biodiversity Huts, Fiordland, also by Michael Kelly, treats a group of 29 huts in the Murchison Mountains and Secretary Island used for intensive efforts to conserve the iconic flightless bird, the Takahe, thought to be extinct but rediscovered in the Murchison Mountains in 1948. The huts were used for deer culling to protect the bird’s food source, and for a range of related scientific and conservation activities.

Landsborough Rangers Hut, by Jackie Breen, West Coast Conservancy, discusses the uniquesequences of uses of this deteriorating hut (used successively over a period of 70 years for sporting deerstalking, road building, and finally deer culling), identified as possibly the last remaining tent frame hut of its type, its association with deer-culling mythology. It does not seem that the recommendation to develop a conservation plan for this hut was ever acted on.

Hut Maintenance by DoC staff and voluntary efforts

Ongoing hut maintenance is the responsibility of staff in the 43 DoC districts. Regular hut inspections identify maintenance needs, which are either attended to on the spot or logged into the AMIS database to generate prioritized work orders. While the system seems to work well in theory, in practice DoC has never had the resources needed to maintain its full inventory of huts. There is always more to do than staffing and funding allow, and setting maintenance priorities can be controversial.

The gap between need and resources — particularly acute in the early years of DoC’s establishment — prompted strategies such as a Recreational Opportunities Review and Visitor Asset Management Programme in the early 2000’s to help the agency set priorities. These processes included opportunities for public comment. Proposals to stop maintaining or remove some huts prompted considerable public concern. In addition to an outcry against DoC’s proposals and rallying support for additional funding for DoC, Kiwi’s reflected on the situation and gradually developed versions of a mantra that is often heard today, essentially: “if we don’t help to maintain the huts we’ll lose them”.

Citizen action to maintain huts

Translating this sentiment into action, and eventually into formal partnerships, is a fascinating story and well told in Shelter from the Storm and other elsewhere. I will simply offer here the barest outline. Longstanding individual and group work on hut maintenance (e.g. recreation, tramping and hunting clubs) intensified and evolved in the 1990’s and 2000’s into a set of active networks. New voices and actors joined in the effort to save remote/endangered huts. Thus, a small but passionate cadre of citizen volunteers cohered into a remarkable movement, prompting DoC to gradually realize that rather than feel criticized, it could tap into a vibrant wellspring of energy and expertise. While organizations such as FMC advocated for DoC maintenance of huts, “others took ownership of the issue and got on with doing them [huts] up”, as Geoff Spearpoint and Rob Brown put it in an excellent coda essay “Preserving the Huts, a Backcountry Partnership” in A Bunk for the Night: A Guide to New Zealand’s Best Backcountry Huts (Potton and Burton, n.d.).

Even the briefest mention of this citizen volunteer movement must mention at least one (of the many) driving forces in cohering grassroots action: Permolat aka Remote Huts, (named for a durable venetian blind material formerly widely used as trail markers), founded in 2003 by Andrew Buglass. A loose network of folks who conduct hut maintenance work on remote huts on the West Coast, they initially took an anarchic “don’t ask, just do it” approach. They have steadily assembled a remarkable track record of re-building several dozen huts and re-cutting neglected tracks. They have also developed an online database of remote huts, and they operate a useful discussion forum for the network.

DoC moves to formalize and support voluntary hut maintenance action

As these citizen volunteer initiatives advanced, a number of understandings and events converged to shift perceptions and set the stage for more formal partnership mechanisms:

The very positive public reception of Shelter from the Storm stirred further local hut maintenance initiatives and public support for DoC huts, multiplying the benefits of public support for DoC.

It became clear that community groups were able to restore remote huts more inexpensively than DoC, due in large part to highly skilled volunteers. An example of this is the work of Derrick Field and his colleagues, all former DoC and NZFS employees, highly skilled tradesmen who are actively maintaining huts.

A recognition that DoC has lost many of the skills of traditional hut building and maintenance through retirement and procedural design changes, and that volunteers can help transmit these skills back to the DoC workforce.

Having DoC regularly engaged with volunteers from the hut community opened up lines of communication and cooperation in very ways.

Some softening of the perception among trampers that DoC’s priorities have turned away from backcountry huts and primarily towards Great Walks and serviced huts.

The establishment of a three-year DoC experiment in formalizing and financially supporting community partnerships, the “Outdoor Recreation Consortium”. Operated by a panel of trampers and DoC folks, this experiment was deemed a success and a good learning opportunity.

As these forces worked their magic over a decade or more, DoC came to further appreciate the public support for their budget requests and the flourishing of voluntary hut maintenance initiatives as positive energy. The tramping community was energized. Rob Brown and others argued that if DoC supported volunteers for biodiversity efforts, why not for huts?

Backcountry Trust: adopting a home in the mountains

Click on the title above to see post on Backcountry Trust.

Hut Wardens paid and unpaid: roles and responsibilities

Click on title above for Hut Warden post.

DoC bookings system and website

As part of DoC’s extensive web site there is a great deal of information about DoC huts, including an online booking system for those huts that are bookable, i.e. Great Walks Huts and Serviced Huts. The well-organized information about NZ huts and the highly effective booking system are a key distinguishing feature of NZ huts: this unified system of 963 huts allows for a centralized, national hut information and booking system that is more comprehensive than that of most other nations (the most comparable website and booking system seems to be that of the DNT in Norway).

This ability to see the DoC hut system as a whole is a key feature of NZ huts. A function of this unique nationally owned and operated system of huts, the web site presents an unusually unified, coherent picture of a very large and varied system. This makes finding out about NZ huts much easier than is the case with most European nations, where the mix of club, public and private huts, lodges, and hotels requires more complicated searching and piecing together information, or, the purchase of guide books, of which there are many.

One of my favorite DoC website features is the remarkable online interactive map of DoC facilities. This has been upgraded recently and is even easier to use. Here is what it looks like:

DoC Online interactive map of facilities, with “huts” box checked. One can click on any of the clusters (going down several levels of clicks) to see individual huts.

A quick overview of the web site and booking system:

There is a web page that explains how to book and pay for a hut stay, including options for purchase of hut passes (with discounts available for members of 9 NZ outdoors organizations, and for YHA members).

There is a search box (see below) that helps find huts to stay in allowing one to search by region, service level, facilities available, and distance from road end.

DoC “Find a Hut to Stay In” search box

Using the above search feature, or searching the DoC site by the name of the hut you wish to learn about, you will find a hut description for most of the 963 huts in the system. These descriptions include: safety alerts in effect, picture of the hut, overview of the hut (including service category), a map showing tracks and nearby huts, and a detailed “about this hut” feature that provides what you will need to know to plan a trip to the hut.

If the hut is bookable there is a link to the booking system. Approximately 90% of NZ huts are not bookable. These operate on a first-come, first-served basis, with an ethos of making room for late-comers.

The booking system is pretty easy to use, allowing you to search availability in a specific hut, indicate the number of bunks you wish to reserve. If you will be visiting a number of bookable huts it is handy to set up an account in advance. The schedule for booking Great Walks Huts is posted well in advance.

*******

This is the end of:

New Zealand Huts Department of Conservation, Part D:

Notes on Ten Selected Operations